简体中文

繁體中文

English

Pусский

日本語

ภาษาไทย

Tiếng Việt

Bahasa Indonesia

Español

हिन्दी

Filippiiniläinen

Français

Deutsch

Português

Türkçe

한국어

العربية

Why Most Traders Fail and How to Increase Trading Success

Abstract:Big financial market volatility and growing access for the average person have made active trading very popular, but the influx of new traders has met with mixed success.

WHAT IS THE NUMBER ONE MISTAKE TRADERS MAKE?

Big financial market volatility and growing access for the average person have made active trading very popular, but the influx of new traders has met with mixed success.

There are certain patterns which may separate profitable traders from those who ultimately lose money. And indeed, there is one particular mistake that in our experience gets repeated time and time again. What is the single most important mistake that led to traders losing money?

Our own human psychology makes it difficult to navigate financial markets, which are filled with uncertainty and risk, and as a result the most common mistakes traders make have to do with poor risk management strategies.

Traders are often correct on the direction of a market, but where the problem lies is in how much profit is made when they are right versus how much they lose when wrong.

Bottom line,traders tend to make less on winning trades than they lose on losing trades.

Before discussing how to solve this problem, it is a good idea to gain a better understanding of why traders tend to make this mistake in the first place.

A SIMPLE WAGER – UNDERSTANDING DECISION MAKING VIA WINNING AND LOSING

We as humans have natural and sometimes illogical tendencies which cloud our decision-making. We will draw on simple yet profound insight which earned a Noble Prize in Economics to illustrate this common shortfall. But first a thought experiment:

What if I offered you a simple wager based on the classic flip of a coin? Assume it is a fair coin which is equally likely to show “Heads” or “Tails”, and I ask you to guess the result of a single flip.

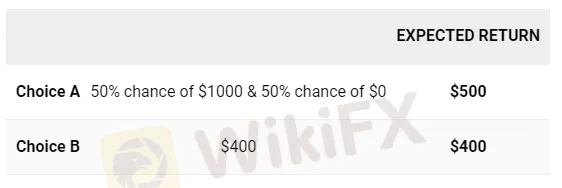

If you guess correctly, you win $1,000. Guess incorrectly, and you receive nothing. But to make things interesting, I give you Choice B—a sure $400 gain. Which would you choose?

From a logical perspective, Choice A makes the most sense mathematically as you can expect to make $500 and thus maximize profit. Choice B isnt wrong per se. With zero risk of loss you could not be faulted for accepting a smaller gain. And it goes without saying you stand the risk of making no profit whatsoever via Choice A—in effect losing the $400 offered in Choice B.

It should then come as little surprise that similar experiments show most will choose “B”. When it comes to gains, we most often become risk averse and take the certain gain. But what of potential losses?

Consider a different approach to the thought experiment. Using the same coin, I offer you equal likelihood of a $1,000 loss and $0 in Choice A. Choice B is a certain $400 loss. Which would you choose?

In this instance, Choice B minimizes losses and thus is the logical choice. And yet similar experiments have shown that most would choose “A”. When it comes to losses, we become ‘risk seeking’. Most avoid risk when it comes to gains yet actively seek risk if it means avoiding a loss.

A hypothetical coin flip exercise is hardly something to lose sleep over, but this natural human behavior and cognitive dissonance is clearly problematic if it extends to real-life decision making. And, it is indeed this dynamic which helps to explain one of the most common mistakes in trading.

Losses hurt psychologically far more than gains give pleasure.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky published what has been called a “seminal paper in behavioral economics” which showed that humans most often made irrational decisions when faced with potential gains and losses. Their work wasnt specific to trading but has clear implications for our studies.

The core concept was simple yet profound: most people make economic decisions not on expected utility but on their attitudes towards winning and losing. It was simply understood that a rational person would make decisions purely based on maximizing gains and minimizing losses, yet this is not the case; and this same inconsistency is seen in the real world with traders…

We ultimately aim to turn a profit in our trades; but to do so, we must force ourselves to work past our natural emotions and act rationally in our trading decisions.

If the ultimate goal were to maximize profits and minimize losses, a $500 gain would completely offset a $500 loss.

This relationship is not linear, however; the illustration below gives us an approximate look at how most might rank their “Pleasure” and “Pain” derived from gains and losses.

PROSPECT THEORY: LOSSES TYPICALLY HURT FAR MORE THAN GAINS GIVE PLEASURE

The negative feeling experienced from a $500 loss can be substantially more than the positive feeling experienced from a $500 gain, and experiencing both would leave most feeling worse despite causing no monetary loss.

In practice, we need to find a way to straighten that utility curve—treat equivalent gains and losses as offsetting and thus become purely rational decision-makers. This is nonetheless far easier said than done.

A HIGH WIN PERCENTAGE SHOULD NOT BE THE PRIMARY GOAL

Your primary goal should be to find trades which give you an edge and present an asymmetrical risk profile.

This means your primary objective should be to achieve a robust “Risk/Reward” (R/R) ratio, which is simply the ratio of how much you have at risk versus how much you gain. Lets say you are right about 50% of the time, a reasonable expectation. Your gains and losses need to have at least a 1:1 risk/reward ratio if you stand to at least break even.

To tilt the math in your favor, a trader making money on roughly 50% of his/her trades needs to aim for a higher unit of reward versus risk, say 1.5:1 or even 2:1 or greater.

Too many traders get hung up on trying to achieve a high win percentage, which is understandable when you think about the research we looked at earlier regarding loss aversion. And, in your own experiences you almost certainly recognize the fact that you don‘t like losing. But from a logical standpoint, it isn’t realistic to expect to be right all the time. Losing is just part of the process, a fact that as a trader you must get comfortable with.

It is more realistic and beneficial to achieve a 45% win rate with a 2:1 R/R ratio, than it is to be right on 65% of your trade ideas, but with only a 1:2 risk/reward profile. In the short run the gratification of “winning” more often may make you feel good, but over time not netting any gains will lead to frustration. And a frustrated mind will almost certainly lead to more mistakes.

The following table illustrates the math well. Over the course of a 20 trade sample, you can see clearly how a favorable risk/reward profile coupled with more losers than winners can be more productive than an unfavorable risk/reward profile coupled with a much greater number of winners. The trader making money on 45% of trades with a 2:1 R:R profile comes out ahead, while the trader with the 65% win rate, but making only half as much on winners versus losers, comes out at a slight net-loss.

Who would you rather be? The trader who ends up positive 7 units but loses more often than they win, or the one who ends up slightly negative but gets the gratification of “being right” more often. The choice appears to be easy.

USE STOPS AND LIMITS – GOOD MONEY MANAGEMENT

Humans arent machines, and working against our natural biases requires effort. Once you have a trading plan that uses a proper reward/risk ratio, the next challenge is to stick to the plan. Remember, it is natural for humans to want to hold on to losses and take profits early, but it makes for bad trading. We must overcome this natural tendency and remove our emotions from trading.

A great way to do this is to set up your trade with Stop-Loss and Limit orders from the beginning. But don‘t set them for the sake of setting them to achieve a specific ratio. You will want to still use your analysis to determine where the most logical prices are to place your stops and limit orders. Many traders use technical analysis, which allows them to identify points on the charts that may invalidate (trigger your stop-loss) or validate your trade (trigger the limit order). Determining your exit points ahead of time will help ensure you pursue the proper reward/risk ratio (1:1 or higher) from the outset. Once you set them, don’t touch them. (One exception: you can move your stop in your favor to lock in profits as the market moves in your favour.)

There will inevitably be times a trade moves against you, triggers your stop loss, and yet ultimately the market reverses in the direction of the trade you were just stopped out of. This can be a frustrating experience, but you have to remember this is a numbers game. Expecting a losing trade to turn in your favor every time exposes you to additional losses, perhaps catastrophic if large enough. To argue against stop losses because they force you to lose is very much self-defeating—this is their very purpose.

Managing your risk in this way is a part of what many traders call “money management”. It is one thing to be on the right side of the market, but practicing poor money management makes it significantly more difficult to ultimately turn a profit.

GAME PLAN: TYING IT ALL TOGETHER

Trade with stops and limits set to a reward/risk ratio of 1:1, and preferably higher

Whenever you place a trade, make sure that you use a stop-loss order. Always make sure that your profit target is at least as far away from your entry price as your stop-loss is, and again, as we stated previously, you should ideally aim for an even larger risk/reward ratio. Then you can choose the market direction correctly only half the time and still net a positive return in your account.

The actual distance you place your stops and limits will depend on the conditions in the market at the time, such as the volatility, and where you see support and resistance. You can apply the same reward/risk ratio to any trade. If you have a stop level 40 points away from entry, you should have a profit target 40 points or more away to achieve at least a 1:1 R/R ratio. If you have a stop level 500 points away, your profit target should be at least 500 points away.

To summarize, get comfortable with the fact that losing is part of trading, set stop-losses and limits to define your risk ahead of time, and aim to achieve proper risk/reward ratios when planning out trades.

Disclaimer:

The views in this article only represent the author's personal views, and do not constitute investment advice on this platform. This platform does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness and timeliness of the information in the article, and will not be liable for any loss caused by the use of or reliance on the information in the article.

WikiFX Broker

Latest News

Top 10 Trading Indicators Every Forex Trader Should Know

ASIC Sues Binance Australia Derivatives for Misclassifying Retail Clients

WikiFX Review: Is FxPro Reliable?

Malaysian-Thai Fraud Syndicate Dismantled, Millions in Losses Reported

Trading frauds topped the list of scams in India- Report Reveals

WikiFX Review: Something You Need to Know About Markets4you

Revolut Leads UK Neobanks in the Digital Banking Revolution

Fusion Markets: Safe Choice or Scam to Avoid?

SEC Approves Hashdex and Franklin Crypto ETFs on Nasdaq

Malaysian Pensioner Loses RM823,000 in Fake Investment Scam

Currency Calculator