简体中文

繁體中文

English

Pусский

日本語

ภาษาไทย

Tiếng Việt

Bahasa Indonesia

Español

हिन्दी

Filippiiniläinen

Français

Deutsch

Português

Türkçe

한국어

العربية

It's official: Trump's tax cuts were an economic bust - Business Insider

Abstract:Anyone with basic knowledge of Keynes and Laffer could've predicted what was just confirmed by GDP: Trump's tax cuts did nothing for the US economy.

US GDP grew by 2.3% in 2019, well below President Trump's promise of 3% growth.The most recent GDP number also proved that the tax cuts championed by Trump and the GOP did nothing to substantially boost the economy.Anyone who looked at history or has some knowledge about economics knew this would be the case.Jared Bernstein is a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Bernstein served as the chief economist and economic adviser to Vice President Joe Biden.This is an opinion column. The thoughts expressed are those of the author.Visit Business Insider's homepage for more stories.On Thursday, we learned that US GDP—the broadest measure of the dollar value of the nation's economy—grew 2.3% last year (on a year-over-year basis).

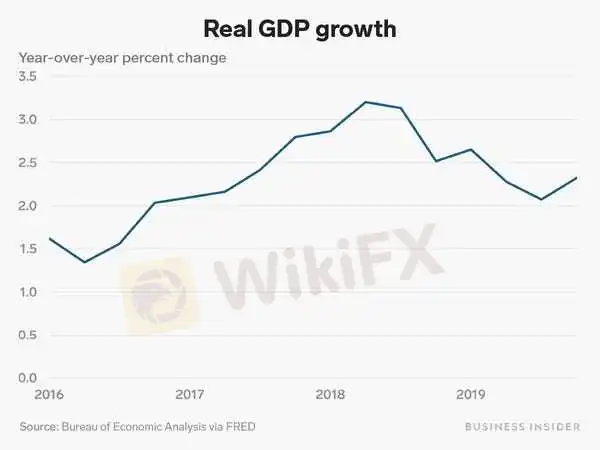

That's a decent growth rate, to be sure, and 2019 marks the 11th year of an historically long expansion. But, as the figure shows, GDP growth slowed last year, and it remains—and is expected to stay—well below the steady 3%growth rate predicted by the Trump administration. In fact, real GDP growth reached 3%only in the middle two quarters of last year.

Andy Kiersz/Business Insider

The administration's bullish forecast was (and is since they've yet to dial it back)based on the belief that the tax cut developed and passed by Trump and the Republicans at the end of 2017 would increase the economy's trend growth rate. A key word there is “trend,” meaning a long-term shift in trajectory as opposed to the pattern you see above.Trump and his economic team have long argued that the tax cuts — especially the big drop in the corporate rate from 35% to 21% would kick off a virtuous cycle delivering lasting growth above the roughly 2 percent that has prevailed for the past two decades. The idea was that lower corporate rates would incentivize more capital investment in things like factories or large equipment and that this added capital stock would permanently boost the economy's productive capacity. You may recognize this as the supply-side-tax-cut scenario popularized by economists Art Laffer and Rober Mundell, wherein tax cuts targeted at investors “trickle down” through the broader economy, lifting growth, wages, and spinning off more tax revenue to help offset the tax cut's initial cost.

Thus far, however, none of the links on the supply-side chain are anywhere to be seen. To the contrary, as the new GDP report showed real business investment has declined for three quarters in a row, the worst such stretch since the last recession.Keynes can tell you why there's no boostSo then why was GDP growth at least temporarily elevated in 2018, the very year the tax cut went into effect? In fact, that's no coincidence. The tax cut did clearly juice growth for a moment. But that moment has passed. It's effects, in other words, were the type associated with John Maynard Keynes, not Laffer.Keynesian economics, in this context, argues that in periods when private sector demand is inadequate to achieve full employment, the government should step in and temporarily make up for the lost demand through deficit spending. Though it's commonly thought that Keynes was just talking about recessions, that's not quite right. His deepest and most lasting insight was that it is not unusual for market economies to underperform, and when they do so, there's a mechanism—public spending—to get back to full capacity.

A key distinction between Keynes and Laffer—other than, if you'll forgive the snark, the former has proved to consistently correct and the latter has not—is that the Keynesian interventions tend to affect the ups and downs of the economic cycle, as opposed to the underlying, trend growth rate. Keynesian fiscal jolts give economies a temporary boost by using, for a limited time, public-sector demand to offset lagging private-sector demand.Though that's not how its advocates sold it, it is what the tax cut did in 2018. As Brookings Institute analysts show, government spending added just under a point to GDP growth in 2018. By the end of last year, that impulse had faded and when it did, as the figure above shows, the growth rate downshifted from around 3% to around 2%. Simply put, the tax cut was all Keynes, no Laffer. It perked up the 2018 growth rate but it did nothing, as the above-cited investment numbers imply, to lift the economy's underlying productive capacity.To be clear, what it did accomplish should not be dismissed. While I've been very critical of the tax cuts' targeting—why exacerbate our inequality problem by lavishing all those tax breaks on the wealthy?—it likely played a key role in taking the unemployment rate down to a 50-year low of 3.5%.

But unless we relentlessly go back to the Keynesian fiscal well year-after-year, we should expect such benefits to fade, as they have.One final point. Given the corporate sector's unwillingness to invest their elevated after-tax earnings, if we really wanted to make a play for boosting structural economic growth—lifting the underlying trend growth rate—we should consider a large public investment program.Investing in productivity-enhancing public goods, including our physical infrastructure, human capital, and most importantly, mitigating the effects of global warming. No one can guarantee that will boost the trend, but it has a much better chance of doing so than regressive tax cuts. Jared Bernstein is a Senior Fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Bernstein served as the Chief Economist and Economic Adviser to Vice President Joe Biden, Executive Director of the White House Task Force on the Middle Class, and a member of President Obama's economic team.

Disclaimer:

The views in this article only represent the author's personal views, and do not constitute investment advice on this platform. This platform does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness and timeliness of the information in the article, and will not be liable for any loss caused by the use of or reliance on the information in the article.

Read more

WikiFX Broker

Latest News

ASIC Sues Binance Australia Derivatives for Misclassifying Retail Clients

WikiFX Review: Is FxPro Reliable?

Malaysian-Thai Fraud Syndicate Dismantled, Millions in Losses Reported

Trading frauds topped the list of scams in India- Report Reveals

AIMS Broker Review

The Hidden Checklist: Five Unconventional Steps to Vet Your Broker

YAMARKETS' Jingle Bells Christmas Offer!

WikiFX Review: Something You Need to Know About Markets4you

Revolut Leads UK Neobanks in the Digital Banking Revolution

Fusion Markets: Safe Choice or Scam to Avoid?

Currency Calculator